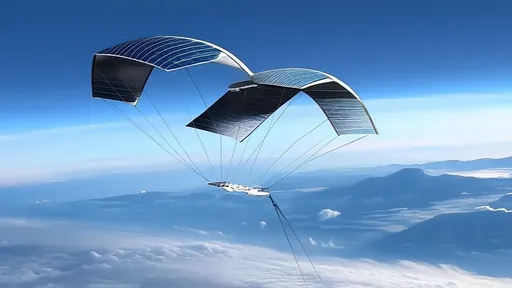

The intersection of biology and renewable energy has taken a bold leap forward with the emergence of bio-photovoltaic systems, particularly those leveraging cyanobacteria-coated building facades. These living solar panels, often referred to as "biogenic solar walls," represent a radical departure from traditional silicon-based photovoltaics. By harnessing photosynthesis in engineered cyanobacteria layers, architects and energy scientists are reimagining urban landscapes as dynamic power generators.

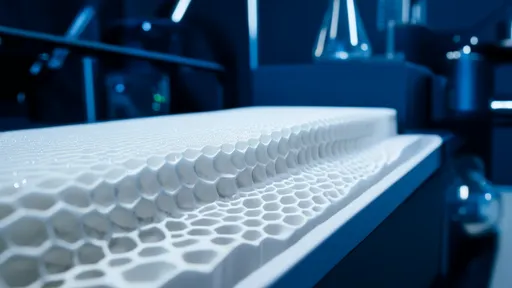

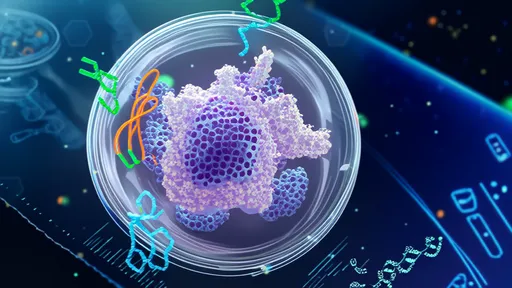

At the heart of this technology lies a simple yet profound biological hack. Cyanobacteria – often called blue-green algae – have been photosynthesizing for billions of years, converting sunlight into chemical energy with remarkable efficiency. When applied as thin-film coatings on building exteriors, these microorganisms generate electrons during photosynthesis that can be captured through bio-compatible electrodes. Unlike conventional solar panels that require rare earth minerals, these biological systems self-replicate, potentially offering a more sustainable path to urban energy production.

The architectural implications are staggering. Imagine glass curtain walls that don't just reflect sunlight but actively harvest it through vibrant, living membranes. Early adopters like the BIQ House in Hamburg have demonstrated the aesthetic potential, with algae-filled panels creating ever-changing green facades that shift color with microbial growth cycles. Beyond aesthetics, these systems provide natural insulation and can even improve air quality through photosynthetic gas exchange.

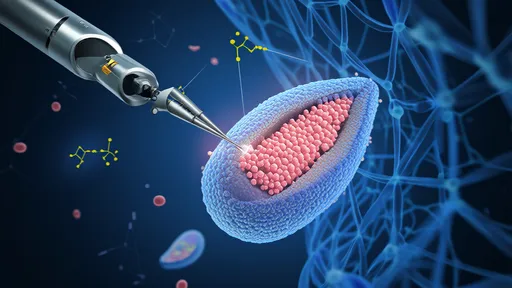

Recent breakthroughs at Cambridge University have pushed the technology's efficiency boundaries. By genetically modifying cyanobacteria strains, researchers achieved sustained electron output even under low-light conditions – a critical advancement for northern latitudes. The modified organisms demonstrate 72% quantum efficiency in light absorption, surpassing most commercial solar cells. When scaled across an entire building facade, preliminary calculations suggest a 50-story structure could generate enough electricity to power its lighting and HVAC systems.

Material scientists have made parallel progress in developing the supporting infrastructure. Flexible, transparent graphene electrodes now allow for seamless integration with curved glass surfaces, while novel hydrogel substrates maintain optimal moisture levels for microbial colonies. The most advanced systems incorporate microfluidic networks that automatically distribute nutrients and remove waste products, creating a semi-closed ecosystem requiring minimal maintenance.

Economic analyses reveal surprising viability. While initial installation costs exceed traditional photovoltaics by approximately 30%, the lifecycle economics tell a different story. The self-repairing nature of biological systems eliminates panel replacement costs, and the integrated water filtration provides additional value streams. In Singapore's PARKROYAL Hotel, the algae facade simultaneously treats greywater while generating electricity, demonstrating the technology's multifunctional potential.

Challenges remain before widespread adoption can occur. Durability concerns in extreme climates, public perception of "living buildings," and regulatory hurdles for genetically modified organisms all present obstacles. However, pilot projects in Berlin, Tokyo, and San Francisco are generating compelling data on real-world performance. The Berlin installation maintained stable output through a full seasonal cycle, only requiring quarterly nutrient replenishment.

As climate pressures intensify, bio-photovoltaic facades offer more than just renewable energy – they represent a philosophical shift in how we conceptualize infrastructure. Buildings become not just energy consumers but active participants in urban ecosystems. With continued refinement, the vision of cities wrapped in photosynthetic skins that breathe, adapt, and power themselves may transition from speculative fiction to practical reality within our lifetimes.

The convergence of synthetic biology, materials science, and architecture in this field hints at broader possibilities. Future iterations might incorporate nitrogen-fixing bacteria to fertilize vertical gardens or glow-in-the-dark genetic modifications for nighttime illumination. As one researcher quipped, "We're not just building structures anymore – we're cultivating them." This paradigm could redefine sustainability, transforming urban centers from concrete jungles into living, energy-producing organisms.

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025